This day (when thou hast made the sign of the Cross, and prepared thyself,) thou hast to meditate upon the condition, and mysteries of this life: that thou may by them understand, how vain the glory of this world is, seeing it is built upon so weak a foundation: and how little account a man ought to make of himself, being as he is subject unto so many miseries.

Now for this purpose thou hast to consider first of the vileness of the original, and birth of man, to wit: the matter whereof he is compounded: the manner of his conception: the griefs, and pains of his birth: the frailty, and miseries of his body: according as hereafter shall be entreated.

Then thou hast to consider the great miseries of the life, that he lives, and chiefly these seven.

First consider how short this life is, seeing the longest term thereof passes not three score and ten, or four score years. For all the rest (if any man's life be drawn a little longer) is but labor and sorrow. And if thou take out of this the time of our infancy, which is rather a life of beasts, than of men, and withal the time, that is spent in sleeping, at which time we have not the use of our senses an reason, thou shalt find that life is a great deal shorter, than it seems unto us. Besides all this, if thou compare this life with the eternity of the life to come, that endures for evermore, it shall scarcely seem so much as a minute: Whereby thou may perceive, how far out of the way those persons are, who to enjoy the little blast of so short a life, do hazard to lose the quiet rest of the blessed life to come, which shall endure everlastingly.

Secondly, consider how uncertain this life is, (which is another misery besides the former. For it is not only of itself very short, but even that very small continuance of life that it has, is not assured, but doubtful. For how many (I pray thee) do come to the age of those threescore and ten, or fourscore years, which we spake of? In how many persons is the web cut off, even at the first, when it is scarcely begun to be woven? How many do pass away out of this world, even in the flower (as they term it) of their age, and in the very blossoming of youth. Ye know not (says our Savior) when our Lord will come, whether in the morning, or at noonday, or at midnight, or at the time of the cock crowing: That is to say: Ye know not whether he will come in the time of infancy, or of childhood, or of youth, or of age. For the better perceiving of this point, it shall be a good help unto thee, to call to mind, how many of thy friends, and acquaintance, are dead, and departed out of this world. And especially remember thy kinsfolk, thy companions, and familiars, and some of the worshipful and famous personages of great estimation in this world, whom death has assaulted, and snatched away in divers ages, and utterly beguiled, and defeated them, of all their fond designs and hopes. I know a certain man, that has made a memorial of all such notable personages, as he has known in this world in all kind of estates, which are now dead: and sometimes he reads their names, or calls them to mind, and in rehearsal of every one of them, he does briefly represent before his eyes, the whole tragedy of their lives, the mockeries, and deceits of this world, and withal the conclusion and end of all worldly things. Whereby he understands what good cause the Apostle had to say: That the figure of this world passes away. [I. Cor. 7:31] In which words he gives us to understand, how little ground, and stay, the affairs of this life have, seeing he would not call theme very things indeed, but only figures, or shows of things, which have no being, but only an appearance, whereby also they are the more deceitful.

Thirdly, consider how frail, and brittle this life is, and thou shalt find, that there is no vessel of glass so frail as it is. Insomuch as a little distemperature of the air, or of the son, the drinking of a cup of cold water, yea the very breath of a sick man is able to spoil us of our life, as we see by daily experience of many persons, whom the least occasion of all these that we have here rehearsed, hath been able to end their lives, and that even in the most flourishing time of their age.

Fourthly, consider how mutable and variable this life is, and how it never continues in one self same stay. For which purpose, thou must consider the great and often alterations, an changes of our bodies, which never continue in one same state and disposition. Consider likewise, how far greater the changes, and mutations of our minds are, which do ever ebb and flow like the Sea, and be continually altered an tossed with divers winds, and surges of passions, that do disquiet, and trouble us every hour. Finally, consider how great the mutation in the whole man is, who is subject to all the alterations of fortune, which never continues in one same being, but always turns her wheel, and, rolls up and down from one place to another. And above all this, consider how continual the moving of our life is, seeing it never rests day or night, but goes always shortening from time to time, and consumes itself like as a garment does with use, and approaches every hour nearer an nearer unto death. Now by this reckoning what else is our life, but as it were a candle that is always wasting and consuming, and the more it burns, and wastes away? What else is our life, but as it were a flower, that buds in the morning and at evening is clean dried up? This very comparison makes the Prophet in the Psalm, where he says, The morning of our infancy passes away like an herb, it blossoms in the morning, and suddenly fades away: and at evening it decays, and waxes hard, and withers away.

Fifthly, consider how deceitful our life is (which peradventure is the worst property it has.) For by this mean it deceives us, in that being in very deed filthy, it seems unto us beautiful: and being but short, every man thinks his own life will be long: and being so miserable (as it is in deed) yet it seem so amiable, that to maintain the same, men will not stick to run through all dangers, travels, and losses, (be they never so great) yea they will not spare to do such things for it, an whereby they are assured to be damned forever and ever in hell fire, and to lose life everlasting.

Sixthly, consider how besides this that our life is so short (as has been said) yet that little time we have to live is also subject unto divers and sundry miseries as well of the mind, as of the body: insomuch as all the same being duly considered, and laid together is nothing else, but a vale of tears, and a main Sea of infinite miseries. S. Ierome declared of Zerxes that most mighty king, (who threw down mountains, and dried up the Seas, that on a time he went up to the top of a high hill, to take a view of his huge army, which he had gathered together of infinite numbers of people. And after that he had well viewed and considered them, it is said that he wept , and being demanded the cause of his weeping, he answered, and said: I weep because I consider that within these hundred years, there shall not one of all this huge army, which I see here present before me, be left alive. Whereupon S. Ierome says these words: O that we might (says he) ascend up to the top of some tower, that were so high, that we might see from thence all the whole earth underneath our feet. From thence should thou see the ruins and miseries of all the world: Thou should see nations destroyed by nations: and kingdoms by kingdoms. Thou should see some hanged, and others murdered: some drowned in the sea, others taken prisoners. In one place thou should see marriages and mirth, in another doleful mourning and lamentation. In one place thou should see some born into this world, and carried to the Church to be christened, in another place thou should see, some others die, and carried to the Church to be buried. Some thou should see exceeding wealthy, and flowing in great abundance of lands and riches, and others again in great poverty, and begging from door do door. To be short, thou should see, not only the huge army of Zerzes, but also all the men, women, and children of the world, that be now alive, within these few years to end their lives, and not to be seen any more in this world.

Consider also all the diseases and calamities that may happen to mens' bodies, and withal all the afflictions, and cares of the mind. Consider likewise the dangers, and perils, that be incident as well to all estates, as also to all the ages of men: and thou shalt see very evidently, the manifold miseries of this life. By the seeing whereof thou shalt perceive how small a thing all that is, that the world is able to give the, and this consideration may cause thee more easily to despise and contemn the same, and all that thou may hope to receive from it.

After all these manifold miseries, and calamities, there succeeds the last misery, that is death, which is as well to the body, as to the soul, of all terrible things the very last and most terrible. For the body shall in a moment be spoiled of all that it has. And of the soul there shall then be made a resolute determination what shall become of it forever and ever.

Of Prayer and Meditation, by Ven. Luis Granada

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Sacred and Immaculate Hearts

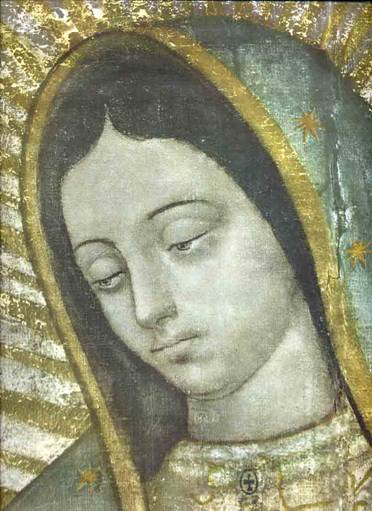

Our Lady of Guadalupe

Pillar of Scourging of Our Lord JESUS

Shroud of Turin