From her infancy she had become mistress of her eyes, and kept them habitually lowered, but without affectation. As she advanced in years and in virtue she became more firmly established in this practice, owing to a resolution she made, when one day in church she happened to look with curiosity, for a moment, at the dress of a little girl who sat next her. She was so angry with herself for this, which seemed to her a crime, that she resolved never more to turn her eyes to look willfully at anyone in this world. From that day forward those innocent eyes remained closed to exterior things and subject to her will. In order to make her use them, a formal command was needed. She then obeyed but only for a few seconds and again, modestly blushing, lowered them. On this account, whoever desired to observe the beauty of her soul that shone in her eyes was obliged to do so while she was in ecstasy, as then she generally kept them raised to Heaven.

As to her sense of taste, nothing could induce her to gratify it. No one was able to ascertain what meat or drink pleased her most, and in order to induce her to partake of what was on the family table it was necessary to press her, otherwise she would deprive herself of what was absolutely necessary. To hide her mortification she used a thousand artifices, feigning to take food while her hands moved but nothing entered her mouth. She went so far as to carry into effect the thought of making a small hole in her spoon, so that the broth might leak through before she brought it to her lips. We have seen that she found pretexts to rise frequently from table, now for one thing, now for another. When in the kitchen helping the servant, she would never taste any of the viands, [articles of food] nor would she ever partake of sweets or fruits that were offered her outside of mealtime. And in order not to be wanting in courtesy by refusal, she managed gracefully and dexterously to get away.

Being a healthy girl she had a natural taste for food and a good appetite. This seemed to her a sort of derangement, and little short of sensuality. With a view to overcome it she would willingly on her part have abstained from taking any nourishment, but this was not allowed her. She thought and rethought, and at last, all gladness at having found a means of remedying her difficulty, she came to propose it to me. Note with what delicate skillfulness she did so.

Father, for a long time Jesus seems to have inspired me to ask you a favor. Don't be vexed with me, for in any case I will do as you wish. There will certainly be no harm in granting my request, but you will have a thousand reasons to bring forward against it: that I am thin, that it is not necessary, etc. But these are valueless reasons--don't wonder at my way of putting it, it is Gemma who writes. Listen, will you be content with my asking Jesus the grace not to let me feel any satisfaction in taking food, as long as I live? Oh, this favor is necessary, and I hope Jesus will tell you to grant it to me. At all events I am content.

As I did not answer this letter, she repeated her request several times. And at last, more to see how such an extraordinary thing would end than from any other motive, I gave my consent. Then the simple child went at once to speak with her Jesus, and at once her prayer was granted. From that day forward she lost all sensibility of palate and never again felt any impression of taste in eating and drinking; neither more nor less than if she had eaten straw or drunk only water. Thus did this young girl mortify a sense that may be considered one of the most difficult to subdue.

The same may be said of the mortification of her other senses. She was never known to gratify herself with the perfume of flower or other scents. As to her sense of speech, she seemed almost to have no tongue, so rigidly did she bridle it; and yet she continually reproached herself with having failed in words, and renewed with earnestness her resolution to curb the erring member. On one occasion she wept an entire day at Our Lord's feet because, not having been able to put off some friends who came to see her, she spent a short time talking with them on innocent matters that seemed to her excessively worldly. "O God," she exclaimed, "and I have allowed myself to speak of such things! Oh tongue, wicked tongue, from this day forward I shall know how to keep thee in bounds!" At another time, humbling herself as she was accustomed to do after her victories in the spiritual combat, she wrote thus: "Yesterday I gained a good victory over my worldly tongue, but I had a hard struggle to keep from speaking! And then I more resolutely renewed my determination never to answer unless questioned. If you only knew what a storm there was between Aunt and me! But silence has overcome all. I have begun, I may tell you, to keep these my resolutions, but with such difficulty!"

The fact was, she began to observe them when she was almost a baby, with only this difference: that then in order not to transgress with her tongue in any dispute, she got out of the way and hid herself; but when more advanced in fears and in virtue, she remained in modest silence, allowing her adversary to cool down. Of curiosity in Gemma it is needless to speak, inasmuch as, dead to herself, she cared for nothing in this world. It all wearied and weighed on her. Games, amusements, recreations she would not hear of; and not even in the days of her infancy did she care for them. One fear at carnival time, an attempt was made to take her with other children to some private theatricals. She was dismayed at it, and so influenced her spiritual Father, convincing him with such strong arguments that, through compassion, he caused her to be left at home alone.

Excerpt from The Life of St. Gemma Galgani, Ch. 17--St. Gemma's Heroic Mortification.

Friday, December 5, 2008

Sacred and Immaculate Hearts

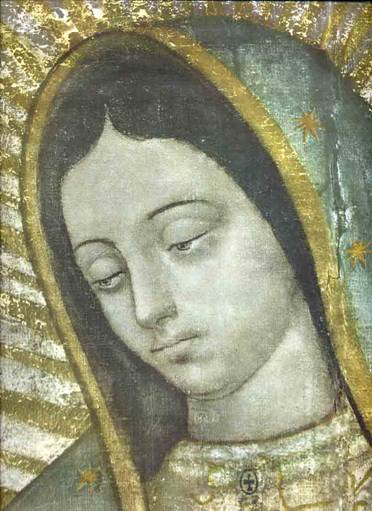

Our Lady of Guadalupe

Pillar of Scourging of Our Lord JESUS

Shroud of Turin