St. Rose of S. Mary

One day having put on a pair of scented gloves in order to oblige her mother, she had no sooner begun to wear them than her hands became cold and benumbed, and soon after she felt in them so violent a heat, that notwithstanding the love of our Saint for sufferings, she was obliged to take off the gloves which caused this torture; and God, to show the blessed Rose that the little breath of vanity which had induced her, under the specious pretext of obedience, to wear these gloves, had inflamed the zeal of her Divine Spouse, showed her the same gloves in the night, surrounded by flames. From that time she never obeyed her mother in anything that was agreeable to the world or to nature, without joining some act of mortification to her obedience. Her mother having absolutely commanded her to remove the pieces of wood which she had secretly put into her pillow, she did so; but she put in their place so great a quantity of wool, and stuffed it in such a manner, that her pillow might have been taken for a log of wood covered with linen, from its hardness.

The stratagem which she practised in order to avoid appearing at assemblies, or accompanying her mother in the visits she paid to her friends and relations, was not less surprising; for she rubbed her eyelids with pimento, which is a very sharp burning sort of Indian pepper: by this means she escaped going into company, for it made her eyes red as fire, and so painful, that she could not bear the light. Her mother having found out this artifice, reprimanded her for it, and mentioned the example of Ferdinand Perez, who had lost his sight by a similar act of indiscretion; Rose answered modestly, "It would be much better for me, my dear mother, to be blind all the rest of my life, than to be obliged to see the vanities and follies of the world."

After this answer, her mother, seeing clearly that it was a repugnance for these visits, and for the dress she was compelled to wear on these occasions, which caused her to inflict this pain on herself, no longer urged her to accompany her, and allowed her to dress as she liked, in a poor stuff' dress, which she wore with great satisfaction; for she sought nothing but contempt and abjection. In all indifferent things S. Rose obeyed willingly, and never received a command from her mother which she did not cheerfully fulfil. Her mother wishing one day to try her obedience, ordered her to embroider some flowers in the wrong way, Rose obeyed blindly, and spoiled her work, and her mother, feigning to be angry, reproved her for it. This truly obedient daughter answered, that she had perceived that her work was good for nothing, but had not dared to disobey the order given her; that it was of no consequence to her in what manner she traced a flower, but that she could not fail in obedience to her mother's orders. For this reason she never began her work without asking her mother's leave, and told one of her friends, who seemed astonished at it, that she did it expressly to join to her work the merit of obedience.

Sacred and Immaculate Hearts

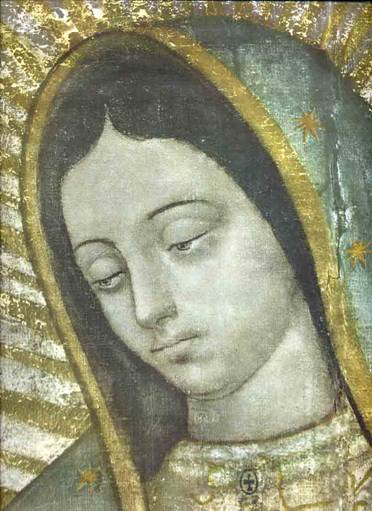

Our Lady of Guadalupe

Pillar of Scourging of Our Lord JESUS

Shroud of Turin