True Spouse of Jesus Christ

On the desire of perfection.

AN ardent desire of perfection is the first

means which a religious should adopt, to acquire

sanctity and to consecrate her whole

being to God. As the sportsman, to hit a bird

in flight, must take aim in advance of his

prey, so a Christian, to make progress in virtue,

should aspire to the highest degree of holiness

which it is in his power to attain, " Who,"

says holy David, " will give me wings like a

dove, and I will fly and be at rest." (Ps. liv.

7.) Who will give me the wings of the dove

to fly to my God, and, divested of all earthly

affection, to repose in the bosom of the Divinity ?

Holy desires are the blessed wings with

which the saints burst every worldly tie, and fly

to the mountain of perfection, where they find

that peace which the world cannot give. But,

how do fervent desires make the soul fly to

God ? " They," says St. Lawrence Justinian, "

supply strength, and render pains light and

tolerable." On the one hand, good desires

give strength and courage, and on the other,

they diminish the labour and fatigue of ascending the mountain of God. Whosoever, through

diffidence of attaining sanctity, does not ardently

desire to become a saint, will never

arrive at perfection. A man who is desirous

of obtaining a valuable treasure which he

knows is to be found at the top of a lofty

mountain, but who, through fear of fatigue and

difficulty, has no desire of ascending, will

never advance a single step towards the wished

for object, but will remain below, in careless

indifference and inactivity. And he who, because

the path of virtue appears to him narrow

and rugged, and difficult to be trodden, does

not desire to climb up the mountain of the

Lord, and to gain the summit of Christian

perfection, will always continue in a state of

tepidity, and will never make the smallest

progress in the way of God.

2. On the contrary, he that does not

endeavour to advance continually in holiness,

will, as we learn from experience, and from all

the masters of spiritual life, go backwards in

the path of virtue, and will be exposed to great

danger of eternal misery. "The path of the

just," says Solomon, "as a shining light

goeth forwards and increaseth even to perfect

day. The way of the wicked is darksome:

they know not when they fall." (Prov. iv. 18, 19.) As light increases constantly from

sunrise to full day, so the path of the saints

always advances ; but, the way of sinners becomes

continually more dark and gloomy, till they know not where they go, and at length

walk into everlasting ruin. " Not to advance,"

says St. Augustine, "is to go back." St. Gregory beautifully explains this maxim of

spiritual life, by comparing a Christian, who

seeks to remain stationary in the path of virtue,

to a man situated in a boat on a rapid river,

and striving to keep the boat always in the

same position. If the boat be not continually

propelled against the current, it will be carried

away in an opposite direction, and consequently, without continual exertion, its station

cannot be maintained. Since the fall of Adam

man is naturally inclined to evil from his birth. "For the imagination and thought of man's

heart are prone to evil from his youth." (Gen.

viii. 21.) If he do not push forward, if he do

not endeavour by incessant efforts to improve

in sanctity, the violence of passion will carry

him back. "Since you do not wish to proceed,"

says St. Bernard addressing a tepid

soul, "you must fail." "By no means," she

replies ; " I wish to live, and to remain in my

present state. I will not consent to be worse;

and I do not desire to be better." "You, then,"

rejoins the Saint, "wish what is impossible." (Epis. 253, ad. Gariv.) Because, in the way

of God, a Christian must either go forward and

advance in virtue, or go backwards and rush

headlong into crime.

3. In seeking eternal salvation, we must,

according to St. Paul, never rest, but must run continually in the way of perfection, that we

may win the prize, and secure an incorruptible

crown. "So run that you may obtain." (1 Cor: ix.'24.) If we fail, the fault will be ours :

for God wills that all be holy and perfect. "

This is the will of God — your sanctification." (1. Thes. iv. 3.) He even commands us to

seek perfection. "Be you therefore perfect,

as also your heavenly Father is perfect." (Mat. v. 48.) He promises and gives, as

the holy Council of Trent teaches, abundant

strength, for the observance of all his commands,

to those who ask it from him. "God

does 'not command impossibilities ; but, by his

precepts, he admonishes you to do what you

can, and to ask what you cannot do ; and he

assists you, that you may be able to do it." (Sess. vi. c. 13.) God does not command

impossibilities; but, by his precepts, he admonishes

us to do what we can by the aid of

his ordinary grace; and when greater helps

are necessary, to seek them by humble prayer.

He will infallibly attend to our petitions, and

enable us to observe all, even the most difficult

of his commandments. Take courage, then,

and adopt the advice of the venerable Father

Torres to a religious who was one of his penitents : "Let us, my child, put on the wings of

strong desires, that, quitting the earth, we

may fly to our Spouse and our Beloved, who

expects us in the blessed kingdom of eternity."

4. St. Augustine teaches, that the life of a good Christian is one continued longing after

perfection. "The whole life," says the Saint, "of a good Christian, is a holy desire." (Tract.

4, in 1. Ep. Joan.) He that cherishes not in his

heart the desire of sanctity, may be a Christian ;

but he cannot be a good one. If this be

true of all the servants of God, how much

more so must it be of religious, who, though it is

not imperative on them to be actually perfect,

are strictly obliged to aspire after perfection. "He that enters the religious state," says St.

Thomas, "is not commanded to have perfect

charity ; but he is bound to tend to it. It is

not," continues the Saint, "obligatory on him

to adopt all the means by which perfection may

be attained ; but, it is his duty to perform the

exercises prescribed by the rule, which, at his

profession, he promised to observe." (2, 2. qu. 186, ar. 2.) Hence, a religious is bound

not only to fulfil her vows, but also to assist

at public prayer ; to make the communions,

and to practise the mortifications ordained by

the rule ; to observe the silence, and to discharge

all the other duties of the community.

5. You will, perhaps, say, that your rule

does not bind under pain of sin. That may

be : but, theologians generally maintain, that,

to transgress without sufficient necessity, even

the rules which of themselves do not impose a

moral obligation, is almost always a venial

fault. Because, the wilful and unnecessary

violation of rule generally proceeds from passion, or from sloth, and consequently must be,

at least, a venial offence. Hence, St. Francis

de Sales, in his entertainments, teaches, that,

though the rule of the visitation did not oblige

under the penalty of sin, still the infraction of

it could not be excused from the guilt of a

venial transgression. " Because," says the

Saint, " by disobedience to her rule, a religious

dishonours the things of God, violates her

profession, disturbs the community, and dissipates

the fruits of the good example which

every one should give." Whoever, then, breaks

the rule in the presence of others, will, according

to the Saint, incur the additional guilt of

scandal. It should be observed, that the

breach of rule may be even a mortal sin, when

it is so frequent as to do serious injury to regular

observance. To violate the rule, through

contempt, is likewise a grievous transgression.

And St. Thomas remarks, that the frequent

infraction of rule practically disposes to the

contempt of it. This is my answer to those

tepid religious who excuse their own irregularities

by saying that the rule imposes no obligation.

The fervent spouses of Jesus Christ

do not inquire whether their rule has the force

of a precept or not : it is enough for them to

know that it is approved by God, and that he

takes complacency in its observance.

6. As it is impossible to arrive at perfection

in any art or science without ardent desires of

its attainment, so no one has ever yet become a saint, but by strong and fervent aspirations

after sanctity. "God," observes St. Teresa, "

ordinarily confers his signal favours on those

only who thirst after his love." "Blessed,"

says the royal Prophet, "is the man whose

help is from thee : in his heart he hath disposed

to ascend by steps, in the vale of tears.

s * * They shall go from virtue to virtue." (Ps. Ixxxiii. 6.) Happy the man who has resolved,

in his soul, to mount the ladder of

perfection : he shall receive abundant aid from

God, and will ascend from virtue to virtue.

Such has been the practice of the saints, and

especially of St. Andrew Avellino, who even

bound himself by vow, "to advance continually

in the way of Christian perfection." (Lect.

5, offic. in die. Testi.) St. Teresa used to say,

that " God rewards, even in this life, every

good desire." It was by good desires that the

saints arrived, in a short time, at a sublime

degree of sanctity. " Being made perfect in a

short space, he fulfilled a long time." (Wis.

iv. 13.) It was thus that Lewis Gonzaga, who

lived but twenty-five years, acquired such perfection,

that St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi,

to whom he appeared in bliss, declared, that

his glory equalled that of most of the saints.

In the vision he said to her : my eminent sanctity

was the fruit of an ardent desire, which I

cherished during my life, of loving God as

much as he deserved to be loved : and, being

unable to love him with that infinite love which he merits, I suffered on earth a continual martyrdom

of love, for which I am now raised to

that transcendent glory which I enjoy.

7. The works of St. Teresa contain, besides

those that have been already adduced, many

beautiful passages on this subject. "Our

thoughts," says the Saint, "should be aspiring:

from great desires all our good will come."

In another place, she says : "We must not

lower our desires, but should trust in God that

by continual exertion we shall, by his grace,

arrive at the sanctity and felicity of the saints."

Again she says: "The Divine Majesty takes

complacency in generous souls who are diffident

in themselves." This great Saint asserted,

that in all her experience she never knew a

timid Christian to attain as much virtue in

many years, as a courageous soul acquires in a

few days. The reading of the lives of the

Saints contributes greatly to infuse courage

into the soul. It will be particularly useful to

read the lives of those who, after being great

sinners, became eminent saints; such as the

lives of St. Mary Magdalen, St. Augustine, St.

Pelagia, St. Mary of Egypt, and especially of

St. Margaret of Cortona, who was for many

years in a state of damnation ; but, even then,

cherished a desire for sanctity ; and who, after

her conversion, flew to perfection with such

rapidity, that she merited to learn by revelation,

even in this life, not only that she was

predestined to glory, but also, that a place was prepared for her among the Seraphim. St.

Teresa says, that the devil seeks to persuade

us that it would be pride in us to desire a

high degree of perfection, or to wish to imitate

the saints. . She adds, that it is a great delusion,

to regard strong desires of sanctity as the

offspring of pride : for, it is not pride in a soul,

diffident of herself, and trusting only in the

power of God, to resolve to walk courageously

in the way of perfection, saying with the Apostle — "

I can do all things in him who strengtheneth me." (Phil. iv. 13.) Of myself I can

do nothing ; but, by his aid I shall be able to

do all things, and, therefore, I resolve to desire

to love him as the saints have loved him.

8. It is very profitable frequently to aspire

after the most exalted virtue ; such as to love

God more than all the saints ; to suffer for his

glory more than all the martyrs ; to bear and

to pardon all injuries ; to embrace every sort

of fatigue and suffering for the sake of saving

a single soul ; and to perform similar acts of

perfect charity. Because, these holy aspirations,

though their object shall never be

attained, are, in the first place, very meritorious

in the sight of God, who glories in men

of good will as much as he abominates a perverse

heart and evil inclinations. Secondly,

because the habit of aspiring to heroic sanctity,

animates and encourages the soul to perform

acts of ordinary and easy virtue. Hence it is of great importance to propose, in the morning, to labour as much as possible for God during

the day ; to resolve to bear patiently all crosses

and contradictions ; to observe constant recollection;

and to make frequent acts of the love

of God. Such was the practice of the seraphic

St. Francis. " He proposed," says St.

Bonaventure, " with the grace of Jesus Christ,

to do great things." St. Teresa asserts, that "

the Lord is as well pleased with good desires,

as with their fulfilment." Oh ! how much

better is it to serve God than to serve the

world. To acquire goods of the earth, to procure

wealth, honours, and applause of men, it

is not enough to pant after them with ardour :

no, to desire, and not to obtain them, only

renders their absence more painful. But, to

merit the riches and the favour of God, it is

sufficient to desire his grace and love. St.

Augustine relates, that, in a convent of hermits,

there were two officers of the emperor's

court, one of whom began to read the life of

St. Antony. " He read," says the holy Doctor, "

and his heart was stripped of the world."

Turning to his companion he said : "What do

we seek ? Can we expect from the emperor

any thing better than his friendship ? Through

how many dangers, are we to reach still greater

perils ? — and how long shall this last ? Fools

that we have been, shall we still continue to

serve the emperor in the midst of so many

labours, fears, and troubles ? We can hope

for nothing better than his favours : and should we obtain it, we would only increase the danger

of our eternal reprobation. It is only with

difficulty that we shall ever procure the patronage

of Csesar ; but, if I will it, behold, I

am, in a moment, the friend of God." Because,

whoever wishes, with a true and resolute

desire, for the friendship of God, instantly

obtains it.

9. I say with a true and resolute desire :

for little profit is derived from the fruitless

desires of slothful souls who always desire to

be saints, but never advance in the way of

God. Of them Solomon says : "The sluggard

willeth and willeth not." (Prov. xiii. 4.) And

again: "Desires kill the slothful." (Prov. xxi. 25.) The tepid religious desires perfection,

but never resolves to adopt the means of its

acquirement. Contemplating its advantages

she desires it ; but, reflecting on the fatigue

necessary for its attainment, she desires it not.

Thus, "she willeth and willeth not." Her

desires of sanctity are not efficacious : they

have for object means of salvation incompatible

with her state. Oh ! she exclaims, were I

in the desert, all my time should be employed

in prayer and in works of penance ; were I in

another convent, I would shut myself up in a

cell to think only of God : if my health were

good, I would practise continual mortifications.

I would wish, she cries, to do all this ; and still

the miserable soul does not fulfil the obligations

af her state. She prays but little ; and is even absent from the prayers of the community;

she neglects communion; is seldom in

the choir, and frequently at the grate and on

the terrace: she practises but little patience

or resignation in her infirmities : in a word, she

daily commits wilful and deliberate faults, but

never labours to correct them. What, then,

will it profit her to desire what is inconsistent

with the duties of her present state, while she

violates strict and imperative obligations? "

Desires kill the slothful." Such useless desires

expose the soul to great danger of everlasting

perdition: because, wasting her time,

and taking complacency in them, she will

neglect the means necessary for the perfection

of her state and for the attainment of eternal

life. " I do not," says St. Francis of Sales, "

approve of the conduct of those who, while

bound by an obligation, or placed in any state,

spend their time in wishing for another manner

of life inconsistent with their duties, or for

exercises incompatible with their present state.

For, these desires dissipate the heart, and make

it languish in the necessary exercises." It is,

then, the duty of a religious to aspire only

after that perfection which is suitable to her

present state, and to her actual obligations ;

and, whether a superior, or a subject, whether

in sickness or in health, the vigour of youth,

or the imbecility of old age, to adopt resolutely

the means of sanctity suitable to her condition

in life. " The devil," says St. Teresa, " sometimes persuades us that we have acquired the

virtue, for example, of patience, because we

determine to suffer a great deal for God. We

feel really convinced that we are ready to

accept any cross, however great, for his sake :

and this conviction makes us quite content :

for the devil assists us to believe that we are

willing to bear all things for God. I advise

you not to trust much to such virtue, nor to

think that you even know it, except in name,

until you see it tried. It will probably happen,

that, on the first occasion of contradiction,

all this patience will fall to the ground."

10. Let us now come to what is most important —

the means to be adopted for acquiring

sanctity. The first means of perfection is

mental prayer, and particularly the meditation

of the claims which God has to our love, and

of the love which he has borne towards us,

especially in the work of redemption. To

redeem us, a God has sacrificed his life in a

sea of sorrows and contempt; and, to obtain

our love, he has gone so far as to make himself

our food. To inflame the soul with the

fire of divine love, these truths must be frequently

meditated. " In my meditation," says

David, "a fire shall flame out." (Ps. xxxviii.

1.) When I contemplate the goodness of my

God, the flames of charity are kindled in my

heart. St. Lewis Gonzaga used to say, that,

to attain eminent sanctity, it is first necessary

to arrive at a high degree of prayer. The second means of perfection is, to renew frequently

your resolution of advancing in divine

love. In this renewal, you will be greatly

assisted by considering, each day, that it is

only then you begin to walk in the path of

virtue. This was the practice of holy David : "And I said now have I begun." (Ps. Ixxvi.

11.) — And was the dying advice of St. Antony

to his monks : " My dear children, figure

to yourselves that each day is the day on which

you began to serve God." The third means

is, to search out continually and scrupulously

the defects of the soul. " Brethren," says St.

Augustine, "examine yourselves with rigour.

Be always displeased with what you are, if you

desire to become what you are not." (De

verb. Apos. Serm. 15.) To arrive at that perfection

which you have not attained, you must

never be satisfied with the virtue you possess. "

For," continues the Saint, " where you have

been pleased with yourself, there you have remained."

Wherever you are content with the

degree of sanctity which you have acquired,

there you will rest, and, taking complacency

in yourself, you will lose the desire of further

perfection. Hence, the holy Doctor adds what

should terrify every tepid soul who, content

with her present virtue, cares but little for her

spiritual advancement : " But if you have said

it is sufficient, you have perished." If you

have said that you have already attained sufficient perfection, you are lost: for, not to advance in the way of God, is to retrograde ;

and, as St. Bernard says, " not to wish to go

forward, is certainly to fail." (Ep. 253, ad Gariv.) Hence, St. Chrysostom exhorts us to

think continually on the virtues which we do

not possess, and never to reflect on the little

good which we have done : for, the thought of

our good works "generates indolence, and

inspires arrogance" — (Hom. xii. in Ep. ad

Phil.) — and serves only to engender sloth in

the way of the Lord, and to swell the heart

with vain glory, which exposes the soul to the

danger of losing the virtues she has acquired. "

He that runs," continues the Saint, " does

not compute the progress he has made, but

the distance he has to travel." He that

aspires after perfection, does not stop to calculate

the proficiency he has made, but directs

all his attention to the virtues he has still to

acquire. Fervent Christians — " as they that

dig a treasure" — (Job, iii. 21) — advance in

virtue as they approach the end of life. "As,"

says St. Gregory, " the man who seeks a treasure,

the deeper he has dug, the more he exerts

himself in the hope of finding it; so the soul,

that pants after holiness, multiplies her efforts

to attain it, in proportion to the advancement

she has made.

11. The fourth means is that which St. Bernard employed to excite his fervour. "He

had," says Surius, "this always in his heart,

and frequently in his mouth — ' Bernard, for what purpose hast thou come ?' " Every religious

should continually ask herself the same

question. I have left the world, and all its

riches and pleasures, to live in the cloister, and

to become a saint — what progress do I make ?

I do not advance in sanctity; no, but, by my

tepidity I expose myself to the danger of eternal

perdition. It will be useful to introduce,

in this place, the example of the venerable Sister

Hyacinth Marescotti, who at first led a

very tepid life in the convent of St. Bernardine,

in Viterbo. She confessed to Father Bianehetti, a Franciscan, who came to the convent

as extraordinary confessor. That holy man

thus addressed her : " Are you a nun ? Are

you not aware that Paradise is not prepared

for vain and proud religious ?" " Then," she

replied, " I have left the world to cast myself

into hell ?" " Yes," rejoined the Father, " that

is the place which is destined for religious who

live like seculars." Reflecting on the words

of the holy man, Sister Hyacinth was struck

with remorse ; and, bewailing her past life, she

made her confession with tearful eyes, and

began from that moment to walk resolutely in

the way of perfection. O how salutary is the

thought of having abandoned the world to

become a saint ! it awakens the tepidity of the

religious, and encourages her to advance continually

in holiness, and to surmount every

obstacle to her ascent up the mountain of God.

Whenever, then, O spouse of Jesus, you meet with difficulties in the practice of obedience, say

to your heart : I have not entered religion to do

ray own will ; if I wished to follow my own

inclinations I should have remained in the

world. But I have come here to do the will

of God, by obedience to my superiors ; aud

this I desire to do in spite of all difficulties.

Whenever you experience the inconveniencies

of poverty, say — I have not left the world, and

retired into the cloister, for the enjoyment of

ease and riches, but to practise poverty for the

love of my Jesus, who, for my sake, became

poorer than I am. When you are rebuked or

treated with contempt, say — I have become a

religious only to receive and bear with patience

the humiliations due to my sins, and thus be

rendered dear to my divine Spouse, who was

so much despised on earth. By this means

you will live to God and die to the world. In

conclusion, I recommend you frequently to

ask yourself this question : what will it profit

me to have abandoned the world, to have confined

myself in the cloister, and to have given

up my liberty, if I do not become a saint, but

if, on the contrary, I expose my soul to everlasting misery, by a careless, and tepid, and

negligent life ?

12. The fifth means, for a religious to attain

sanctity, is frequently to call to mind and

anew the sentiments of fervour, and the desires

of perfection which she felt when she first entered religion. The Abbot Agatho being once asked by a monk for a rule of conduct in religion,

replied : " See what you were on the day

you left the world, and persevere in the dispositions

you then entertained." Remember, O

consecrated virgin, the resolutions which you

made, on the day you retired from the world,

to seek nothing but God, to have no will but

his, and to suffer all manner of contempt and

hardship for the love of Jesus Christ. This

thought, as we learn from the lives of the

Fathers — (Part ii. §. 201)— brought back to

his first fervour, a young monk who had fallen

into tepidity. When he first determined to

retire into a monastery, his mother strongly

opposed his design, and endeavoured by various

reasons to shew that it was his bounden duty

not to abandon her. To all her arguments he

replied : I am resolved to save my soul. And,

in spite of her opposition, he entered religion.

But, after some time, his ardour cooled, and

tepidity stole into his heart. His mother died,

and, a little after her death, he was seized with

a dangerous malady. In his sickness, he

thought he saw himself before the judgment

seat of God, and his mother reproaching him

with the violation of his first resolution : My

son, said she, you have forgotten the words, I

have resolved to save my soul, by which you

replied to all my entreaties. You have become

a religious, and is it thus you live ? He recovered

from his infirmity, and, reflecting on his

first fervour, he commenced a life of holiness,

Sacred and Immaculate Hearts

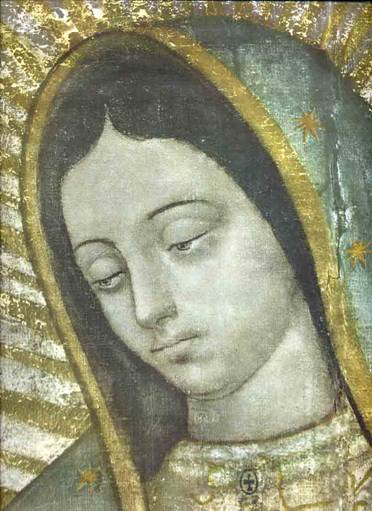

Our Lady of Guadalupe

Pillar of Scourging of Our Lord JESUS

Shroud of Turin