The Second Treatise containing a consideration of the miseries of man's life herein the former meditation is declared more at large.

How great the miseries are, that the nature of mankind is subject unto by reason of sin, there is no tongue able to express. And therefore S. Gregory said very well, that only our two first parents, Adam, and Eve, (who knew by experience the noble condition, and state, wherein almighty God created man,) understood perfectly the miseries of man. Because they by calling to mind the felicity and prosperous estate of that life, which they had once enjoyed, saw more clearly the miseries of the banishment, wherein they remained through sin. But the children of these our two miserable parents, as they never knew what thing prosperity, and good happe was, but were always fostered, and brought up in misery: so they know not, what thing misery is, because they never knew what prosperity was. Yea many of them are as it were persons in a mere frenzy, so far void of sense, as they would (if it were possible) continue perpetually in this life, and make this place of banishment their country, and this prison their dwelling house, because they understand not the miseries thereof. Wherefore like as they that are accustomed to dwell in places of unsavory and stinking air, do feel no pain nor trouble of it, by reason of the custom, and use, they have thereof: even so these miserable persons understand not the miseries of this life, because they are so inured, and accustomed to live in them.

Now that thou may not likewise fall into this foul deceit, nor into other greater inconveniences that are wont to follow hereof: Consider (I pray thee with good attention) the multitude of these miseries: and before all other, consider and weigh the miseries, that are in the first beginning, and birth of man, and afterwards the conditions of the life he lives.

To begin this matter therefore at the very original, Consider first of what matter man's body is compounded. For by the worthiness, or baseness of the matter, oftentimes the condition of the work is known. The holy scripture says, that almighty God created man of the slime, or dirt of the earth. Now of all the elements, earth is the most base, and inferior: and among all the parts of the earth, slime is the most base, and vile. Whereby it may appear, that almighty God created man of the most vile, and basest thing of the world. Insomuch as even the kings, the emperors, and the popes, be they never so high, famous, and royal, are even slime, and dirt of the earth. And this thing understood the Egyptians right well, of whom it is written, that when they celebrated yearly the feast of their nativity, they carried in their hands certain herbs, that grow in mire and slimy ditches, to signify thereby, the likeness and affinity, that men have with weeds, and slimy dirt: which is the common father both to weeds, and men. Wherefore if the matter of which we are made, be so base, and vile, whereof art thou so proud, thou dust, and ashes? Whereof art thou so lofty, thou stinking wed, and dirty slime?

Now as concerning the manner, and workmanship, wherewith the work of this matter is wrought, it is not to be committed to writing, neither yet to be considered upon, but to be passed over with silence, and closing up our eyes, that we behold not so filthy a thing as it is. If men knew how to be ashamed of a thing which they ought of reason to be ashamed of, surely they would be ashamed of nothing more, than to consider the manner how they were conceived. Concerning which point I will touch one thing only, and that is, that whereas our merciful Lord, and Savior, came into this world to take upon him all our miseries, for to discharge us of them, only this was the thing, that he would in no wise take upon him. And whereas he disdained not to be buffeted, and spitted upon, and to be reputed for the basest of all men, only this he thought was unseemly, and not meet for his majesty, to wit, if he should have been conceived in such manner, and order, as men are. Now as touching the substance and food wherewith mens' bodies are nourished, before they be born into this world, it is not so clean a thing, as that it ought once to be named. No more ought a number of other unclean things, that are daily seen at the time of our birth.

Let us now come to the birth of a man, and first entry into the world. Tell me I pray thee, what thing is more miserable, than to see a woman in her travail, when she brings forth her child? O what sharp agonies and bitter pangs does she feel? What painful tossings and throws does she make? What dangerous gripes and qualms is she in? What pitiful shrikes and groanings does she utter? I omit here to speak of many monstrous, strange, and over thwart births. For if I should make rehearsal of them, I should never make an end. And yet all this notwithstanding when the seely creature comes into the world, it comes (God knows) weeping, and crying, poor, naked, weak, and miserable: it is utterly destitute and in necessity of all things, and unable to do any thing. Other living things are born with shows upon their feet, and apparel upon their back: some with wool: others with scales: others with feathers: others with leather: others with shells: insomuch as the very trees come forth covered with a rynde or bark, yea and sometimes for failing they be double barked: only man is born stark naked, without any other kind of garment in the world, but only a skin, which is all riveled, foul, and loathsome to behold, wherein he comes lapped at the time of his birth. With these ornaments creeps he into the world, who after his coming, grows unto such fond ambition, and pride, that a whole world is scarcely able to satisfy him.

Moreover, other living things at the very hour of their coming into this world, are able immediately to seek for such things as they stand in need of, and have ability to do the same: Some can go: others can swim: others can fly: to be short, each one of them is able without any instructor to seek for such things, as it has need of; only man knows nothing, neither is he able to do any thing, but must of necessity be carried in other folk's arms. How long time is it before he can learn to go? And yet he must begin to crawl upon all four feet, before he can go upon two. How long time is it, before he can speak so much as one word? And not only before he can speak, but also before he can tell how to put meat into his own mouth, unless some others do help him? One thing only I must confess he can do of himself, that is, he can cry and weep. This is the first thing he does, and this is the thing only he can do without any teacher. And although he can also laugh of himself, yet can he not do it, before he be forty days old, notwithstanding that he is evermore weeping from he first hour of his coming into this world. Whereby thou may understand, how far more prompt, and ready our nature is to pewling, and weeping, than to joy, and mirth. O mere folly, and madness of men, (says a Wiseman) who of so poor, naked, and base beginning, do persuade themselves, that they are born to be proud.

Now as concerning the very body of man, (whereof men esteem themselves so much, and take such a vain conceit) I would thou should consider with indifferent eyes, what our bodies are in very deed, how gay and beautiful soever they appear to our outward sight. Tell me (I pray thee) what other thing is the body of a man, but only a corrupt and tainted vessel, which incontinently sours ,and corrupts whatsoever liquor is poured into it? What other thing is man's body, but only a filthy dunghill, covered over with snow, which outwardly appears white, and within is full of filth, and uncleanness? What muckhill is so filthy? What sink avoids out of it such filthy gear through all his channels, as a man's body does by several means, and ways? The trees, the herbs, yea and certain living beasts also do yield out of them very sweet and pleasant savours; but man yields, and avoids from him, such loathsome, and foul stinking stuff, as he seems truly none other thing, but only a fountain of all sluttishness and filthiness.

It is written of a great wise philosopher called Plotinus, that he was ashamed of the condition, and baseness of his body, insomuch as he was very unwilling to hear any talk of his lineage, and pedigree; neither could he ever be induced with any persuasions to give his consent that any man should portrait him out in picture; saying, that it was sufficient, that he himself carried with him all the days of his life a thing so filthy and so unworthy of the nobleness of his soul, although he were no bound to leave behind him a perpetual remembrance of his own dishonor.

It is written also of the holy abbot Isidorus, that upon a time while he was at meat he was not able to refrain from weeping, and being demanded why he wept, he answered; I weep, because I am ashamed to be here feeding upon the corruptible meat of company of Angels, and to feed upon heavenly food with them.

Of Prayer and Meditation, by Ven. Luis Granada (pdf)

Sacred and Immaculate Hearts

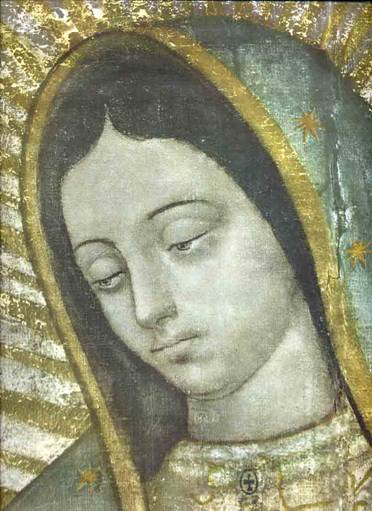

Our Lady of Guadalupe

Pillar of Scourging of Our Lord JESUS

Shroud of Turin